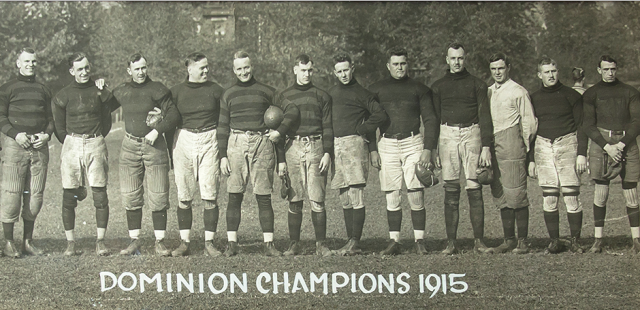

1915 Grey Cup – Hamilton Tigers vs Toronto Rugby and Athletic Association

The 7th Grey Cup was played on November 20, 1915, before 2,808 fans at Varsity Stadium in Toronto, Ontario to determine the championship of Canadian football.

The Hamilton Tigers defeated the Toronto Rugby and Athletic Association 13 to 7.

Source The National Post

The score of the 1915 Grey Cup was flown back to Hamilton by carrier pigeon. At the final whistle, the home fans chased the referee into the locker room. Out on the field, still slick from the autumn rain, the visitors celebrated.

The Cup would not be hoisted again in victory for five more years. Few days in an ensuing century of football were as remarkable as November 20, 1915 even if many Canadians were focused on something else.

“RUSSIA IS PREPARING TO RAISE MILLIONS OF FRESH TROOPS,” read the banner headline of the Saturday morning Toronto World. What would become the First World War was little more than a year old, and hostilities fixated on a sliver of land in southeast Europe. Serbia and other Allied forces, including Russia, struggled to withstand an Austro-German assault.

On page eight of that day’s World was a sports briefing: “Three Rugby Finals on Today’s Program.” The preview ran in one slender column, sandwiched between men’s clothing advertisements: soft-brimmed hats on Yonge Street for $2.50, boots at Eaton’s for $1.95. The day’s featured match was for the Grey Cup.

So it was that the Hamilton Tigers and the Toronto Rowing and Athletic Association prepared to play.

It was not expected to be close, as is often the case when ordinary meets extraordinary. Toronto had faced just one other team in 1915. They split four regular season games with the Hamilton Rowing Club, their only opponent in the Ontario Rugby Football Union, before winning a playoff rubber match.

Their reward was a date with the Tigers, champions of the “Big Four” conference the Interprovincial Rugby Football Union three years running. They arrived in Toronto 6-0 on the season, scoring double the points of nearly every team in Canada. “Tigers are great campaigners on any old kind of field, and will enter the deciding game strong favourites,” the World’s preview declared.

If the Grey Cup can be considered at all iconic today, it was not then. Only Canadian Rugby Union members specifically, the winners of the ORFU and the IRFU could play for it, excluding all teams west of Ontario until 1921. “It wasn’t really the big thing it has become today,” said Canadian football author Frank Cosentino, a Cup-winning quarterback in the 1960s.

At any rate, the early road to the Grey Cup ran exclusively through southern Ontario. Six teams challenged for the first seven championships; all were from Toronto or Hamilton. One was the Tigers, who shredded the Toronto Parkdale Canoe Club 44-2 at home in 1913.

Two years later, at Toronto’s Varsity Stadium, they may have banked on another blowout.

It was a surprise, then, when the rowers trotted into halftime with a 4-1 lead, kicking a field goal and capitalizing on Hamilton’s inability to hold onto the ball. Conditions were wet “greasy,” the World wrote afterward and the Tigers’ attack, built on speed and guile, did not look very fast or cunning early on.

It looked helter skelter, but there was some sort of system to it

Hamilton’s strength was its halfbacks: the McKelveys, Johnny and “Chicken”, flanking Sammy Manson, the most dangerous player in the game. Manson was 23 in the fall of 1915, and Toronto’s best bet to counter him was 20-year-old George Bickle, a formidable rusher and kicker himself.

Manson and Bickle were prototypical stars of rugby football, when touchdowns were “tries” and worth five points, not six. Blocking was banned past the line of scrimmage. Entire defences would assemble along the line before plays, rather than station some players deep. There was no such thing as a forward pass.

The backs, as such, controlled every play. They could look for holes in the defence to breeze or bull through, lateral to a teammate in open space or punt mid-play into the barren defensive backfield, where anyone behind the ball when it was kicked could chase it for a long gain.

“It looked helter skelter, but there was some sort of system to it,” Cosentino said. Whoever mastered the system usually won.

It was the boot of “Soldier” Bickle, as the World tabbed him on game day, that gave Toronto its early lead; a Manson rouge was all the Tigers had to show at half. Chicken McKelvey, slowed by injury, had hobbled off within the first 10 minutes. He was replaced by a substitute named Norman Lutz.

The game had drawn a crowd from Hamilton, a vocal minority of the 2,808 fans. With them, they brought a flock of messenger pigeons: the fastest means of carrying news of victory back home.

“The winged carriers hesitated at first, circling the stadium for a half-hour before heading west with their halftime report,” author Michael Januska wrote in the book Grey Cup Century, asserting that the birds must have known their team was trailing.

The Tiger players, meanwhile, returned to the field with greater purpose.

Two runs was all it took for them to break Toronto’s pressure: first, a long dash from Johnny McKelvey, and then another by Jack Erskine. A Scottish immigrant and a blacksmith’s assistant by trade, Erskine was also a barrel-chested wing, and he fell into the end zone for the game’s first try.

Toronto thought otherwise. Erskine had fumbled at the goal line, defenders argued to the referee, a man named Ewart “Reddy” Dixon. The ball rolled out of the end zone, they said: it should be a single Hamilton point, not a try. But Dixon paid them no heed.

It was apparently not considered curious or alarming that Dixon was a Hamilton native, or that he had played for the Tigers and won the Grey Cup with them in 1913 before taking up officiating. “Before the game President (Hal) DeGruchy of the Toronto club expressed himself as thoroughly satisfied with the officials the Canadian Rugby Union had appointed,” the Toronto Daily Star reported.

The sentiment did not last long. Toronto mustered two singles in the third quarter both from captain DeGruchy, Bickle’s backfield mate to make the score 7-6: close enough to harbour late dreams of an upset, and close enough to feel cheated when the Tigers struck again.

The next controversy centred on Lutz, Hamilton’s substitute. Since entering for the limping Chicken McKelvey, his two-way play had “turned the tide in favor of the Tigers,” the World wrote. It was his turn to try for the decisive blow.

After a long punt return by Manson, Lutz took the ball from the snap, saw a hole and raced 20 yards into the end zone. The defenders howled. Hamilton was guilty of offside interference, they pleaded to Dixon a lineman had blocked past the line of scrimmage, opening the gap for Lutz. Thinking the run would be negated, they had stopped defending mid-play.

Again, Dixon paid them no heed.

At 12-6 (the convert missed), Toronto had now gone more than three-quarters of the game without reaching the Hamilton end zone. They could not mount a comeback through kicks alone.

Except they almost did were it not, post-game accounts claimed, for the addled judgment of Dixon. Only a few minutes remained when Toronto sent a long punt into the end zone, toward the usually sure-handed Manson.

“But he slipped, the ball took an awkward bounce and rolled toward (Toronto wing) Dode Burkart, who only had to fall on the ball for an apparent touchdown,” wrote Stephen Thiele in Heroes of the Game: A History of the Grey Cup. “Again, there was no whistle.” In Dixon’s mind, play had not stopped, not until Tigers defenders pulled Burkart from the ground and dumped him back on the one-yard line.

It was a first down, not a touchdown, and while Toronto now had three chances to gain one yard a virtual gimme, even without the option of passing Dixon’s ruling had finally rendered them mad. Two runs up the middle were stopped immediately. The third play, a pitch to the side, was snuffed out behind the line.

Verbal insults were exchanged and according to those on the field, Dixon began to taunt the angry mob

The teams traded rouges as time wound to zero. The game ended 13-7.

Dixon’s day was far from done. “Feeling ran so high that a Toronto crowd so far forgot the city’s reputation as the abode of good sportsmen that they staged a perfectly good little mob scene with Referee Dixon as the centre of the maelstrom of hate,” the Daily Star recalled the scene.

“Verbal insults were exchanged and according to those on the field, Dixon began to taunt the angry mob,” Thiele wrote. “Police had to use their batons freely to disperse the crowd and rescue him. With many fans still in hot pursuit, Dixon was rushed to the relative sanctuary of the Toronto dressing room.”

Outside, some Toronto fans brawled with joyous Hamiltonians. The home locker room, meanwhile, was deathly quiet until Dixon, unable to keep silent, dared anyone to show him where he had missed a call.

“Crawford,” Thiele wrote, referring to a Toronto wing, “rose to his feet, stepped over to Dixon and retorted, ‘You were the best man on the Tiger team, and if you don’t like it you can lump it.’ Dixon stood silent realizing that Crawford was willing to back his words with his fists.”

Monday’s Toronto World headline was succinct: “HAMILTON TIGERS EARN RUGBP TITLE; Torontos Got Jump in Fisrt Period, But Could Not Maintain the Lead.” The result and the typos were preserved in ink.

Canadian football is a game tied inherently to its past. The Grey Cup came before the CFL by several decades, and as such, unusual names line its oldest rings. Queen’s University, champions for three straight years from 1922 to 1924. In 1925 and 1926, the Ottawa Senators, whose hockey counterparts won their final Stanley Cup the year after.

And from 1916 to 1919: nothing.

“Times were changing and the world was now marching into a war that stole the best and brightest of a generation,” Januska wrote in Grey Cup Century. Regular-season play was suspended, and gate proceeds from the 1915 Grey Cup were donated to the families of soldiers fighting overseas. Games could no longer be prioritized.

“There was this idea that if you were fit and strong enough to be playing football, you should be joining the greater and grimmer game,” said Nic Clarke, a historian at the Canadian War Museum. “If you’re physically capable of doing that, the argument is always going to be, ‘Well, why the heck aren’t you in uniform?’”

The roll call of players turned soldiers reads like a lineup, with positions swapped out for places and dates. Samuel Ryckman Manson, enlisted in Hamilton, January 1916. George Berry Bickle, Toronto, August 1915, committed to service before his breakout season. Jack Erskine, drafted under the Military Service Act, joined in Niagara Falls in February 1918. On it goes.

Records are spotty, and their fates uncertain, but a Library and Archives Canada death registry shows most soldiers who played for the 1915 Grey Cup likely survived the war. Some, like Manson, returned to football. The Cup challenge resumed in 1920. The Tigers won three more 1928, 1929 and 1932 and merged with another Hamilton club in 1950. They became the Tiger-Cats.

But before any of that, there was a championship to savour in 1915 and one more matter to address.

When the Tigers had won the Grey Cup in 1913, it was still in the hands of the University of Toronto, champions from 1909 to 1911, whose players refused to surrender the trophy until they were beaten for it directly. That took until 1914.

“The Hamilton boys, though, would find a way to gain a small measure of revenge,” author Stephen Brunt wrote in 100 Grey Cups: This is Our Game. Finally holding the Cup, the Tigers brought it to a Hamilton carver, and asked him to do two things: add a plaque for their win in 1915, and another for 1908: the year the Tigers won Canada’s last dominion championship, before the Grey Cup came to be.

“The extra inscription wasn’t noticed until years later, when the Cup was taken in for repairs in 1951,” Brunt wrote, “and at that point the decision was made to leave it, as a permanent record of the Canadian game’s idiosyncratic history.”